My NRIC number was public for four days. Should it have been?

Last Friday, I was getting off the bus in downtown Houston when I received a rather alarming message from a friend in Singapore.

To set the context: my National Registration Identity Card (NRIC) number — what most will consider the equivalent of a Social Security Number in the United States, and the National Insurance Number in the United Kingdom — was on a public government website, publicly accessible free of charge to anyone who knew where to look. This was not a data breach, but a feature that was added to the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA) portal, which is used by businesses to look up information about other businesses and individuals.

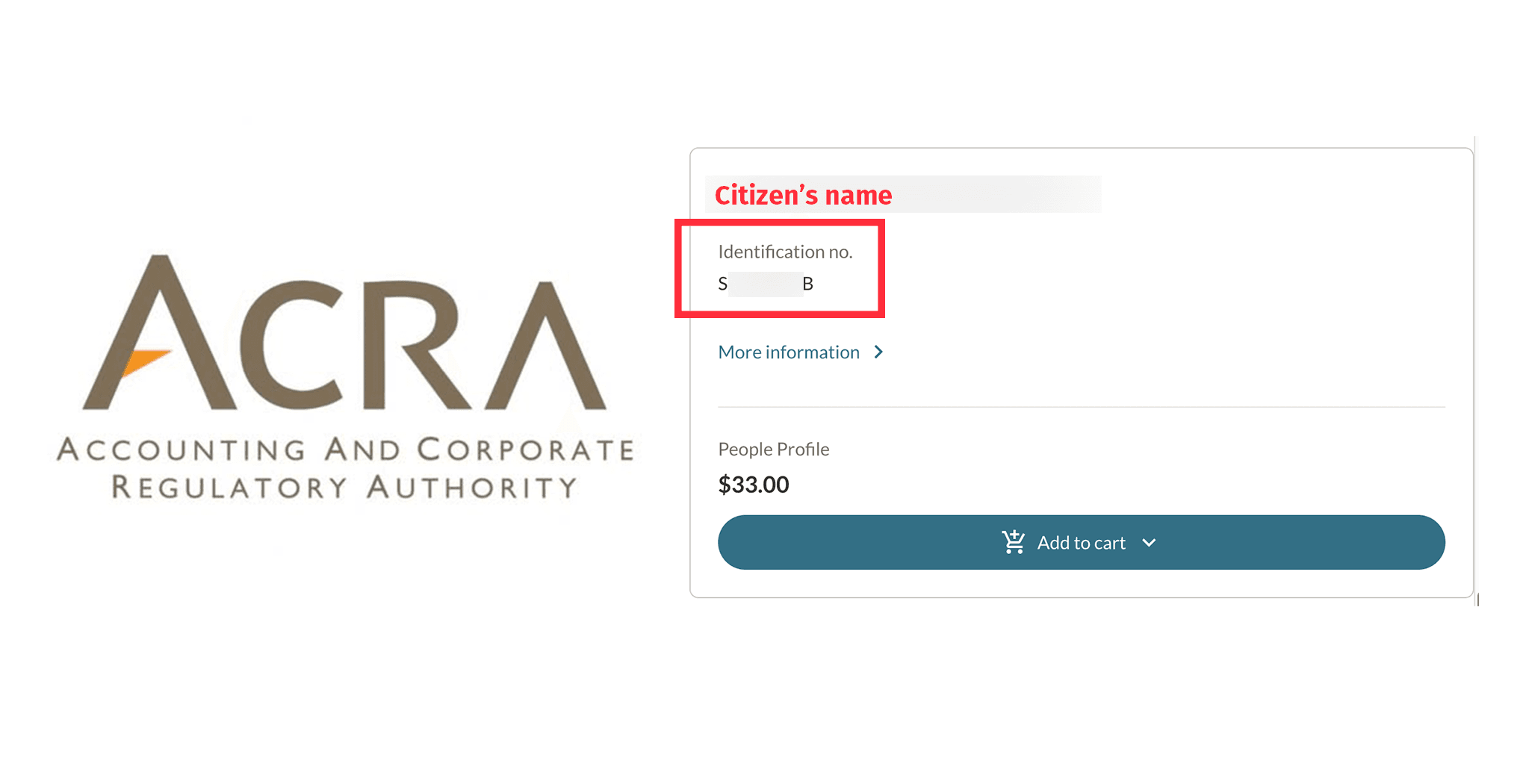

The feature was released on the 9th of December, and on the 13th of December, Mothership reported on it. You could search for the name of any person, and if they were associated with a business, their NRIC number would be displayed free of charge, and a "full profile" — with additional information, like a citizen's residential address — is for sale for S$33.

My information was probably on there because I registered a business in Singapore a while ago which I no longer actively operate. According to the latest data from ACRA, as of the end of 2023, there were 588,764 registered businesses in Singapore, with a significant portion being owned by Singaporeans. This means that hundreds of thousands of individuals had their NRIC numbers exposed, just like me.

This feature has since been disabled, but the damage has probably already been done. This was public for four days, and it is not unreasonable to assume that someone could have scraped much of the data in that time. While this is disturbing on its own, what I'm more concerned about is the subsequent response from the government, and the discussion around the sensitivity of NRIC numbers. I think this is relevant to many of my readers, even if you are not from Singapore, because it involves a slightly more nuanced discussion about the differences between security and privacy.

Secret or not?

Following the disabling of the feature, the Ministry of Digital Development and Information (MDDI) responded to queries from the media.

MDDI said in its statement that NRIC numbers are meant to be used to identify individuals and "should be used as such".

"As a unique identifier, the NRIC number is assumed to be known, just as our real names are known," said the ministry.

"There should therefore not be any sensitivity in having one’s full NRIC number made public, in the same way that we routinely share and reveal our full names to others."

It added that it has been a practice for some time to use masked NRIC numbers. But there is no need to mask the number, nor is there much value in doing so, said MDDI.

"Using some basic algorithms, one can make a good guess at the full NRIC number from the masked number, especially if one also knows the year of birth of the person."

This is why public agencies are phasing out the use of masked NRIC numbers, so as to avoid giving a "false sense of security", said MDDI.

This is an interesting perspective, which came as a shock to many. For years, the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) has made it illegal for organizations to collect, use, or disclose NRIC numbers without a valid reason, with a financial penalty of up to S$1 million (although government agencies are exempt) — this has led many to treat NRIC numbers as sensitive information that should be kept secret.

This means that many organizations that do collect NRIC numbers often use them as part of identity verification. My banking app, for example, asks for my NRIC and a 6-digit PIN to log in. My insurance company sends me policy documents in a password-protected PDF, with part of the password being my NRIC number. Given the current state of affairs, I'll be very concerned if my NRIC number is leaked.

But I'm not the person you should be worried about here — it's the people who are likely to believe the scammer on the other end of the phone who claims to be from the government and backs that up by reciting their NRIC number. Or worse, people who set their banking PIN to contain their birth year: this sort of feature makes it much easier to spray-and-pray NRIC and PIN combinations to gain access to someone's bank account, since the birth year is the first two digits of the NRIC number.

That said, it is true that full NRIC numbers are easily guessable given the masked number and the year of birth. The algorithm for calculating the checksum (the last letter of the NRIC number) is publicly available, and the structure of the NRIC number is well-known. But I imagine that for many, the contention is not about whether the NRIC is masked or not, but about whether it should be public at all. For instance, one might feel slightly safer disclosing only the street they live on, rather than their full address, but that doesn't mean they should be comfortable with their street address being publicly searchable by anyone on the internet.

The ministry said it recognises that some Singaporeans have "long treated" the NRIC number as private and confidential information, and will need time to adjust to this "new way of thinking".

In 2025, MDDI and the Personal Data Protection Commission (PDPC) will be carrying out public education about the purpose of the NRIC number and "how it should be used freely as a personal identifier".

Perhaps the timing just wasn't right, and there is a perfectly reasonable world where the NRIC number is public and everyone is fine with it. But this probably doesn't have to be either/or. Most web services use email addresses as unique account identifiers, and one probably won't consider their email address to be top-secret information. Yet, it'll likely be a bad idea to make the email addresses of all registered users public. So if the NRIC number is to be used as a unique identifier, maybe it should be treated with at least the same level of care.

Scalability

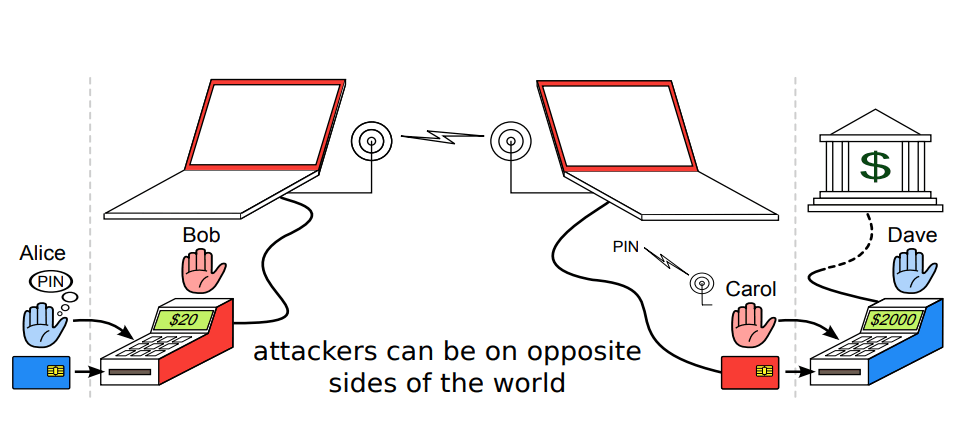

When we think about threat models, it's often tempting to think about the worst-case scenario. But the reality is that most people are not going to be targeted by a sophisticated attacker who is willing to invest significant time and resources — and those who are probably either have the means to protect themselves or have bigger problems to worry about. The real danger is in the low-hanging fruit that can be exploited at scale.

For instance, think about the chip-and-pin terminal relay attack. It's a conceptually obvious decades-old attack that involves intercepting the communication between a chip card and a terminal, and relaying it to another terminal to make a transaction for a higher amount. But it's not used in practice because it's not scalable: you need to be physically close to the victim, and you need to have a way to relay the communication in real-time. So while it's a cool attack, no one's bothered fixing it because it's not a real threat.

On the other hand, attacks like the no-PIN attack which only require a stolen card to be used were a much bigger problem, so the industry had to change the protocol entirely.

The reason it'll be a bad idea to make the email addresses of all registered users public is because it enables a stupidly simple attack at scale: you can now send phishing emails to everyone who has ever signed up for your service, and you'll probably get a few people to click on the link. You can also spray passwords from a data breach against all the email addresses you have, and you'll probably get a few hits. So while any one individual's email address is probably not that sensitive, making all email addresses easily scrapable would be really bad (and if you could dump the email addresses of all users of a popular service, you could probably get a handsome bug bounty or if you're less ethical, make a lot of money selling that data).

At the same time, for the individual, letting one person know your email address is probably not a big deal — you can just block them, right? But if you let everyone know your email address, that's probably called an invasion of privacy. The scale at which the information is exposed matters.

In fact, there is probably a lot of "unique identifier" information that can be considered "not sensitive" on its own, but you'll probably not be comfortable with being made public. Some simple examples:

- Your phone number uniquely identifies you among all people who have a phone number, but you probably don't want any random person — maybe a creep you met at a bar that one time — to be able to look up your phone number and call you.

- Your home address is unique to the people who live with you — likely your family — but you probably don't want people or unsolicited mail to show up at your door uninvited.

While it's true that these examples facilitate some kind of other interaction — a phone number is used to call you, and a home address is used to send you mail — and the NRIC doesn't have more direct utility, the point is that the NRIC number has become part of what most people consider to be their personal, private information. In fact, even the NRIC number itself already contains one's birth year. And when enough of these pieces of information are put together, they can be used to paint a very detailed picture of a person's life — the holy grail of scammers, stalkers, and data brokers.

It's fine for one website to store metadata about me, keyed with my NRIC number. But if that website, and a bunch of other websites, make my NRIC and its associated metadata public, then I'd expect to be able to find a good profile of myself available for sale on the internet or the dark web. And that's stretching my comfort zone.

Privacy vs. security

"Likewise, the NRIC number should not be used as passwords, just as we should not be using our names as passwords. If the NRIC number is used for authentication, it would have to be kept a secret, which would defeat its main purpose as a unique identifier," MDDI added.

Subsequently, the PDPC also made a similar point about authentication:

The commission noted that it had previously taken action against organisations which used NRIC numbers for authentication and "breached their data protection obligations".

It said: "A person’s name and NRIC number identifies who the person is. Authentication is about proving you are who you claim to be. This requires proof of identity, for example, through a password, a security token or biometric data.

"As the NRIC number is not a secret, it should not be used by an organisation for authentication purposes."

I believe that for many technical folk, this wouldn't be a controversial statement. Indeed, using NRIC numbers as "what you know" in authentication is inherently flawed. If the intent is to make NRIC numbers public, there is much work to be done to ensure that systems we use are secure. Imagine ordering a plate of chicken rice and getting a queue number. In the ideal case, you should not be able to just walk up to the counter and say "I'm number 42". You should have to present your queue number or receipt. But most places don't do this, and the same is true for many systems that depend on NRIC numbers for authentication.

But this seems to be conflating the issues of privacy and security. While there is much to be said about the current flawed implementations of NRIC-based authentication, the fact that we want to use NRIC numbers as usernames or account identifiers doesn't change many's expectations of privacy.

Going by this reasoning, should identifiers like passport numbers, biometric data stored on my phone, and even credit card numbers be public too? Afterall, all of these require at least one second factor of authentication to be useful (a convincing face, access to my physical phone, CVV number).

I think the distinction between privacy and security is important. Privacy is about controlling who has access to your information, while security is about ensuring that only the right people have access to your information. The two are related, but they are not the same. One would generally consider Google to be secure — I don't lose sleep over the idea that someone might hack into my Google account — but we all know that Google sells a lot of our data to advertisers. So while I have strong security controls over my Google account, I have very little privacy control over it.

The main contention then is about whether we should consider NRIC numbers to be personally identifiable information (PII) that we should expect reasonable privacy over. For me at least, the answer is yes. At the very least, the correlation between my NRIC number and other information about me, in the hands of unsavoury characters, would create inherent risk that I would not be comfortable with.

This is echoed in the PDPC's guidelines on NRIC numbers:

As the NRIC number is a permanent and irreplaceable identifier which can potentially be used to unlock large amounts of information relating to the individual, the collection, use and disclosure of an individual’s NRIC number is of special concern. Indiscriminate or negligent handling of NRIC numbers increases the risk of unintended disclosure with the result that NRIC numbers may be obtained and used for illegal activities such asidentity theft and fraud.

It does not matter how secure our systems are if we are not careful about what information we expose to the world. Even if all systems on our small corner of the world are perfectly secure, having lived and worked overseas, my NRIC has been used by foreign governments and organizations as a form of identification and for tax purposes as an independent contractor. Can we be certain that all systems in all countries make the same assumptions about the sensitivity (or lack thereof) of the NRIC number, when in most other countries, similar identifiers are considered private? One would have to expect systems to know that a Singaporean NRIC number is far less sensitive than a US Social Security Number, or UK National Insurance Number, and implement different security controls based on that. But that's a big ask.

More importantly, it is impossible to patch human nature. Ever notice how banks always have a disclaimer that they will never call you to ask for your PIN? Yet, people still fall for scams! No matter how much you try to educate people, there will always be someone who doesn't get the memo. A big part of modern security engineering is designing systems that are secure by default — making it hard for people to make mistakes — because we've learnt as an industry that education can only go so far.

Where I stand

My folks are getting old. Of all things privacy-related, I lose the most sleep over the idea that they might fall for impersonation scams that have been on the rise in Singapore.

I know women in my life who will be deeply uncomfortable with what a highly motivated individual might do when given access to just a little bit more information about them.

Just because I have a secure lock on my door doesn't mean I want to risk someone bringing a lockpick to my doorstep. People used to have to pay good money for this information on the dark web — surely Economics 101 tells us that there is value in this information. Now it's intended to be free for all. Us cybersecurity folk tend to be a paranoid bunch, but I think the idea that we shouldn't let people know more about us than they need to should not be controversial.

Let me know what you think. Should the NRIC number be public?